Technical Background

Wood engraving and Printing.

This page provides a brief introduction to the technology of Bewick's image production. Photographs of boxwood blocks in various states, of his tools and of the printing presses used in print workshops of the period are shown. Bewick did not invent boxwood engraving as such, but he developed techniques of drawing, cutting and printing which attracted much attention. It led to the new phenomenon of the popular illustrated book where letterpress text and engraved woodblock could be set into the same printer's forme to be printed together, thus reducing the cost of illustration (and therefore of publication) and changing the appearance of the printed page. This technique went on to dominate nineteenth century illustrated book production.

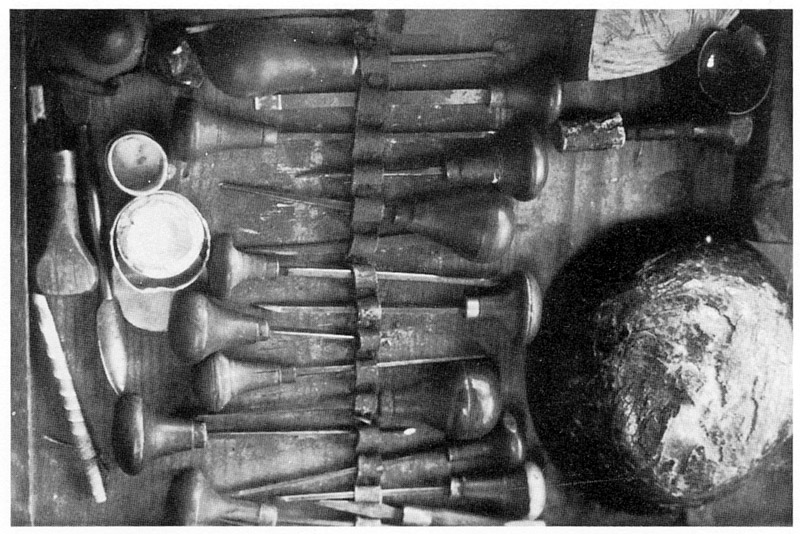

The Tools

The box of Bewick's tools in the Pease collection is in the condition he left it at the time of his death in 1828. Though used specifically for engraving on the end-grain of boxwood, they are in fact very similar to the range of metal cutting tools used in copper-engraving (at which, of course, Bewick was also skilled). The large round object on the left of the photograph is a leather-covered lead casting used as a rest for the woodblock while cutting.The block needs frequent turning and angling, controlled by the left hand, while the right hand holds the burin or graver which makes the incisions. Photograph: The Pease Collection

The Materials

Bewick used boxwood cut across the grain (instead of along the grain). This is a very hard, close-grained wood which allows for fine-detailed cutting which will survive many impressions without showing signs of wear. It has the limitation that box does not grow normally to a great thickness of bole, so when cut across to make a block it is rare to find one much larger than 6 inches (15 cms) across and normally they are 3 to 4 inches (9 to 10 cms). Bewick was not the first to use this material - it had been used by printers for ornamental letters, etc., since the late 17th century. He was the first to show the artistic potential of the medium and indeed the commercial potential in making illustrated books of high quality at relatively low prices. Photograph: T.N. Lawrence & Son

The Methods: Drawing

Bewick started by producing a rough sketch of his subject on paper for the purpose of arranging the composition. This would then be re-drawn on another piece of paper in the exact size for transfer on to the wood surface. The transfer drawings might be coloured, though this was not necessary. The process of transfer to the wood was by blacking the reverse side with a pencil, laying the paper (right side up) to the block and using a scriber to follow the outlines of the drawing hard enough to leave a trace of the blacking on the wood surface, which was sometimes primed with chalk. This process actually focussed on the outlines and much of the detail was transferred simply by eye and memory during the cutting process. Photograph: Iain Bain

The Methods: Engraving

Most of Bewick's blocks were cut in the white-line method, i.e. he would cut away the wood where white was to be seen in the printed image, leaving a raised surface to take the ink. This enabled him to deal with flaws in the wood by adjusting the design to ensure that a white area occupied the flawed patch. He also lowered the surface of the block in certain areas of the image so as to soften the imprint, de-emphasise elements of the composition, and re-inforce the distinction between background and foreground. Careful comparative scrutiny of images enables us to recognise individual styles of cutting, and even changes of style in the same person as time passes. The block could be set into the forme (with any type required) for placing in the press. Photograph: Joicey Museum

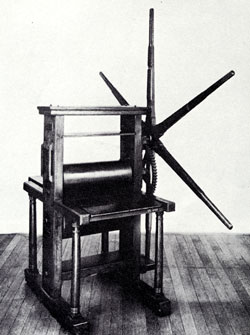

Copper-engraving

This is an entirely different process, known as intaglio, using a special press to produce the high pressure required. The image is cut into the metal plate so that the resulting hollows can be filled with ink and the top surface wiped clean to print white in the final print. The paper has to be dampened and put under pressure, via a roller, to suck the ink out of the hollows - and the deeper the hollow the more ink can be sucked up. This cannot be done on the same machine at the same time as the letterpress printing (as can be done with the wood block). It can, however, achieve much finer detail than even the best wood-engraving. Photograph: Science Museum, London